It is assumed that any nation would prefer as its leader someone with an impeccable record, free of imperfections. However, at certain times in history the establishment’s outcast was the one chosen to do what needed to be done. Reasons vary, but the root cause is constant – the establishment accepted by the dominant power has run its course.

When the power behind the establishment fails to accept its decay and inevitable end, the agent for change is often the extreme risk taker, willing to suffer tribulations including incarceration, or worse.

If they persist and survive, agents for change often achieve their objective of ending a decayed regime, and in the process, they rise to power. Their rise and eventual position of leadership simply indicate that a new cycle is starting. Whether the new cycle is of benefit to the people of a nation depends on the sincerity and ability of the new leader.

An interesting report dated May 16, 2018, by the news network France 24, From Prison to Power: Leaders who Served Time, gives five examples of individuals who famously went from incarceration to leadership. Of the five, here is, very briefly, the story of the better-known three:

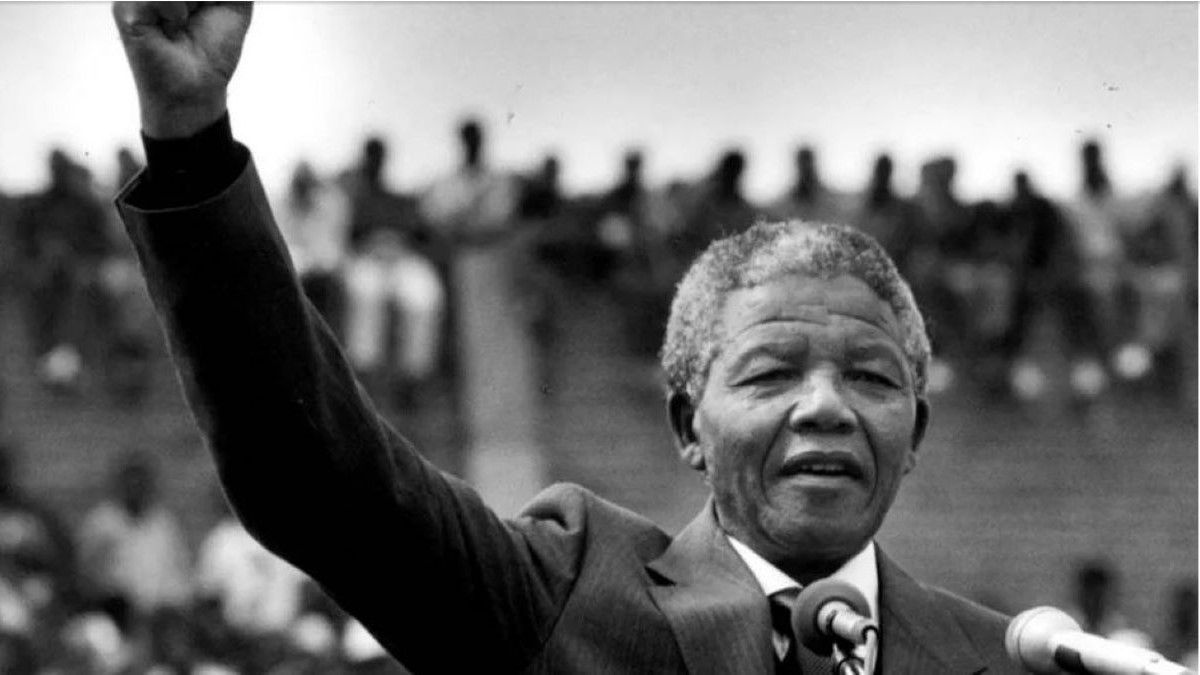

Nelson Mandela founded the paramilitary wing of the African National Congress with the mission to fight against the South African apartheid government. After 27 years of incarceration, Mandela became in 1994 South Africa’s president in the country’s first multiracial election. One of his most popular quotes is, “I am not a saint, unless you think of a saint as a sinner who keeps on trying.”

Jawaharlal Nehru’s opposition to British colonial rule in India landed him in jail in 1921. His continued civil disobedience campaigns alongside Mahatma Gandhi cost him nearly a decade of incarceration. When in 1947 India finally achieved independence, Nehru was elected the country’s first prime minister, a position he held until his death in 1964. Nehru’s efforts could be summarized in one of his quotes: “The policy of being too cautious is the greatest risk of all.”

Vaclav Havel was a Czech playwright, essayist, and poet. He was also a dissident. During the 1970s and 1980s Havel was arrested several times by the ruling Soviet regime and spent four years in prison. But December 29, 1989, saw the peaceful overthrow of communist rule. Vaclav Havel was democratically elected president. The Czech transition to democratic rule was achieved non-violently – the “otherwise” of what Havel once said: “Evil must be confronted in its womb and, if it can’t be done otherwise, then it has to be dealt with by the use of force.”

Regimes, like people, become sclerotic. As time passes, regimes grow increasingly inflexible and unresponsive. They become wedded to ideologies that might no longer fit time and place. At some point, the regime simply collapses, as did the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War; or suffers a violent demise, as did the French monarchy during the reign of Louis XVI.

Agents of change, like the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev or the French Revolution’s Maximilien Robespierre play major roles in ending a regime that is in an untenable level of decay. Like Mandela, Nehru and Havel, agents often rise to power to start a new cycle.

For clarification, it is useful to note that the organic cycle of regimes from natural birth to natural demise has no relation to forceful takeovers by outside agents. For example, the rise and fall of the Roman Empire exemplifies a regime’s organic cycle. Conversely, inorganic takeovers include colonization of other people’s land by European powers starting around the 1500s, or the more socially acceptable “partitioning” of territories as occurred after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, or today’s Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Picture: Nelson Mandela in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa, two days after his release from prison. Image from In Pictures: 30 years since Nelson Mandela became a free man, AlJazeera, February 11, 2020.